In a dimly lit warehouse near Seattle, Richard Berger’s remarkable collection of colossal minerals awaits a new home. Berger is actively seeking a benefactor with the means to purchase the “Masterpieces of the Earth” and establish a museum to display these natural wonders.

Unlike many enthusiasts, Berger’s fascination with minerals didn’t begin in childhood. Growing up in the Bronx, he first encountered quartz in his twenties. In 1968, while disillusioned with medical school, he stumbled upon a “rock shop” sign on a Wyoming back road. Intrigued, he stopped and was mesmerized by a small crystal, which he described as the most beautiful thing he had ever seen.

Fast forward over four decades, and Berger, alongside his wife, has amassed one of the world’s most prestigious private collections of crystals, fossils, and natural formations. This collection is anything but small, featuring an amethyst geode the size of a Smart car, a nearly 4-foot-wide ammonite fossil, a 700-pound pyrite crystal cluster that sparkles like a disco ball, and a 3.5-ton quartz crystal that seems to glow from within. Known as “The Masterpieces of the Earth,” the collection comprises over 100 specimens, each chosen for its extraordinary size, beauty, or quality, and is now available for purchase.

A Vision for a Museum

Berger’s goal is not just to sell to the highest bidder; he dreams of keeping the collection in the Northwest and creating a museum to house it. “Every time I think about it leaving the country, my heart sinks,” he shared, noting offers from China. “I would like to see it become part of Seattle’s cultural legacy.”

Seattle has a history of philanthropists funding museums. Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen’s EMP Museum celebrates rock ‘n’ roll, while fellow Microsoft alum Charles Simonyi funded a space exploration gallery at the Museum of Flight. However, it’s uncertain who might champion minerals and fossils.

Challenges in Selling Mineral Collections

Elizabeth Nesbitt, curator of geology at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, acknowledges the difficulty in selling mineral collections, citing the limited number of buyers. Some museums are even selling their own collections, although others, like the Perot Museum of Nature and Science in Dallas and Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History, are expanding their mineralogy sections.

“The appeal of minerals has shifted from a niche interest to a more mainstream fascination,” said Peabody Director David Skelly, who recently acquired two pieces from Berger, including a massive selenite rose. “These specimens have a showstopping quality,” he added.

Financial Hurdles and Ethical Considerations

Berger has not disclosed the asking price for his collection, but it is in the millions. Few museums can afford even a single large specimen without donor support. Yale’s expansion, for instance, is funded by a $4 million gift from a wealthy alumnus. The Burke Museum, focused more on scientific value, would consider accepting Berger’s collection if a donor covered the cost, despite ethical concerns about the private sale of fossils.

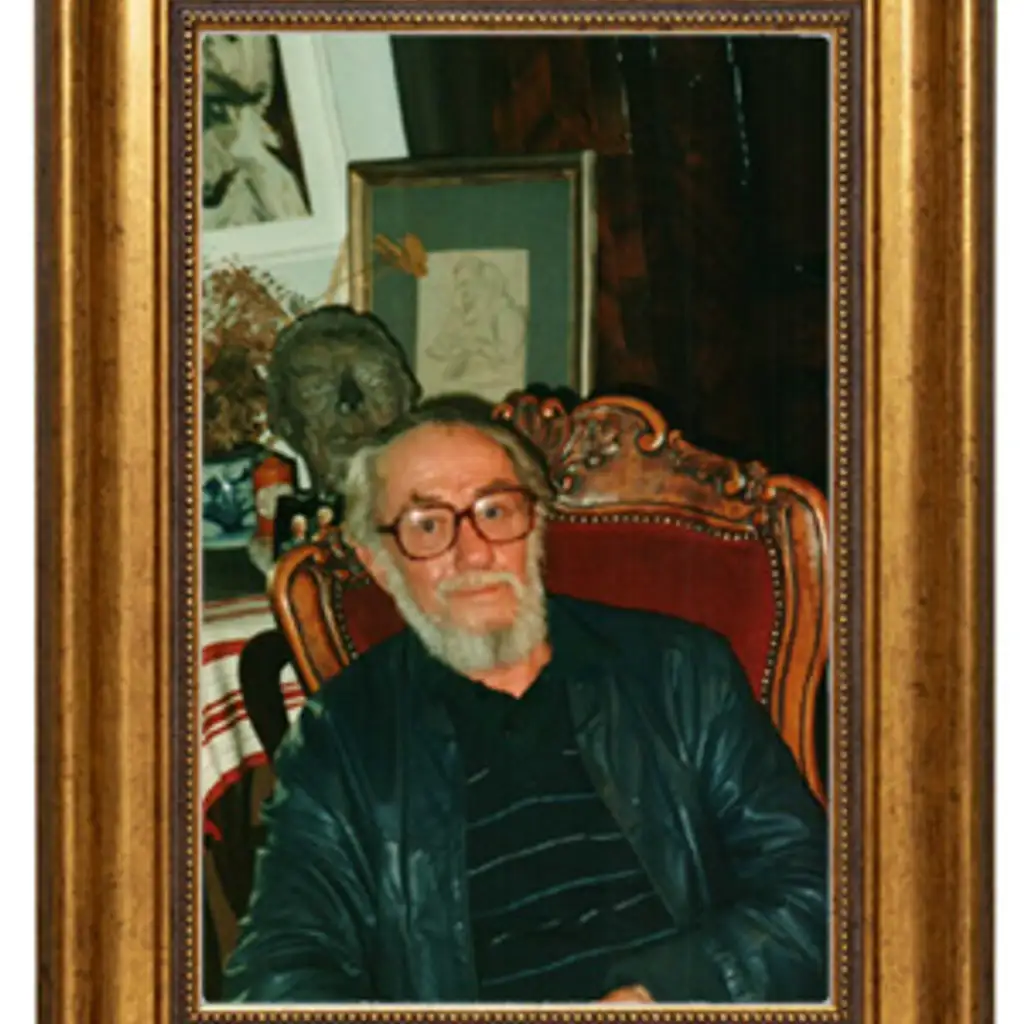

Currently, the collection is stored in a 6,000-square-foot warehouse near Seattle, inaccessible to the public. Berger and his wife reside in a modest 315-square-foot cottage to minimize expenses. “Every dime I have, all my assets since 1980, have gone into this collection,” he stated.

A Global Collection

Berger’s journey began after his Wyoming epiphany, leading him to abandon medical school and search for increasingly elaborate crystals and fossils. In the 1980s, he ran a successful gallery in Manhattan, selling fossils and minerals to fund his quest for natural masterpieces. The couple moved to Seattle in 1988, transporting their collection in five tractor-trailers and opened a gallery in the Alexis Hotel, which they operated until 1995.

Many pieces in the collection were discovered at industrial mining sites. In the early days, Berger traveled extensively, from Tennessee to the Peruvian Andes, to find rare specimens. Eventually, people began contacting him with unique finds, such as the Fontainebleau concretions from France, which resemble psychedelic ice cream cones.

Berger’s collection is a veritable “United Nations of minerals,” with specimens sourced from around the globe, including a wall-sized fossil tableau from Wyoming and giant ammonites from Mexico. The collection spans vast time periods, with some crystals over half a billion years old.

A Legacy for Seattle

Berger hopes any new owner will preserve the collection’s integrity. He envisions a custom exhibit space with dramatic lighting and serene areas for contemplation. “My core desire is for this to be an experience that tens of thousands can enjoy in a place of peace and beauty,” he said. “I want to alert Seattle to its existence and see if there’s interest in keeping it here.”