Upgrading VRAM is also essential for anyone looking to maximize display options on the Quadra 700. Adding six 256KB VRAM SIMMs, along with the 512KB on the logic board, brings the VRAM to 2MB. This allows for higher resolutions and more colors, such as a 256-color setup at 1152×870 resolution on a “two-page” 21-inch display or thousands of colors at lower resolutions like 832×624.

Operating system support on the Quadra 700 extends to Mac OS 8.1, the last version compatible with Motorola processors, introducing features like the “Platinum” interface and the HFS+ file system. Connectivity is made easier with its onboard Ethernet port, though the AAUI interface requires a transceiver to convert it to a more modern 10BASE-T RJ45 connection, allowing the system to connect to modern networks with DHCP.

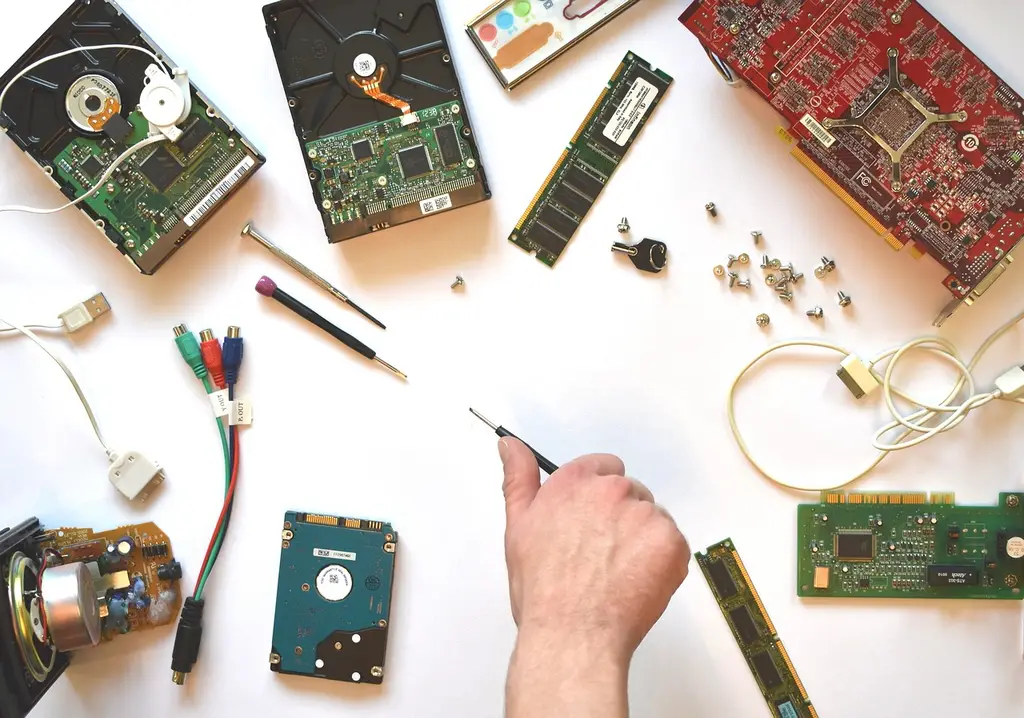

SCSI support has long been a hallmark of vintage Macs, and with the Quadra 700, daisy-chaining SCSI devices is simple. This setup includes a 4x Apple CD-ROM, a 1GB external hard drive, and an Iomega Zip 100 drive, while an additional internal 1GB hard drive increases storage to 2GB. NuBus slots expand the Quadra’s functionality further, accommodating additional network and video cards, like the 24-bit display card used for dual CRT monitors.

For further enhancements, options include adding a Fast SCSI bus, high-resolution video cards, or even overclocking the processor from 25MHz to 33MHz. PowerPC upgrade cards were also available for Quadra models, boosting performance to Power Macintosh levels, but the cost and effort required mean these upgrades remain niche.

Despite being around 30 years old, the Quadra 700 is still capable of basic office tasks, distraction-free writing, light browsing with proxy services, and limited use of creative software. Simple word processors like Microsoft Word 5.0 are especially suited to the system’s capabilities, providing a distraction-free, cloudless writing environment.

Networking capabilities allow for FTP file transfers and email, albeit with careful IMAP and SMTP configuration. Browsers like Netscape Communicator 4.04 or Internet Explorer 3.01 allow access to select websites, though HTTPS limitations restrict compatibility with modern sites. However, tools like theoldnet.com allow browsing of archived websites, offering a glimpse into the past web.

The Quadra 700 performs well with resource-demanding software like Infini-D for 3D rendering, though it’s limited by the processor speed of 25MHz. While tasks like rendering a simple scene are possible, they take minutes compared to modern systems’ milliseconds. Similarly, Photoshop is usable for basic photo retouching, though larger JPEGs can challenge the CPU.

In multimedia, the Quadra 700 can play AIFF files and MP3s, although the latter will occupy most of the CPU, making it impractical for multitasking. Full-motion video is at the limit of its capabilities, performing best with low-resolution Cinepak-encoded files stored on a RAM disk to overcome SCSI bottlenecks.

Gaming on the Quadra 700 is a highlight for retro enthusiasts, with titles like Civilization II and SimCity 2000 taking full advantage of its dual-monitor setup and color depth. Classic games like Wolfenstein 3D run smoothly at lower resolutions, though later titles such as Duke Nukem 3D push the system beyond its limits.

For those invested in vintage Mac collecting, the Quadra 700 provides a robust and capable system for early ’90s software and gaming, offering a nostalgic yet functional experience.